OK, just seven minutes left before I get logged off at the internet cafe but...

A HUGE Happy New Year to everyone! What a great year it's been indeed and thanks to everyone for your friendship, encouragement, support, thoughts, prayers, gifts, and all, all the rest. We are so blessed to have such wonderful families and such a great extended group of friends. Thanks to everyone who played a role in making 2006 one of the best years ever. Just a quick thank you list then:

To our parents and grandparents for all your support, for the logistical legwork you always have to do for us, the care packages, the emails... for being great parents.

To our brothers for your friendship, welcome, and kindness. We are blessed to have brothers who are also friends. (Congrats to Mika and Sian for getting engaged this Christmas! Hooray! And welcome Sian to our family.)

To David Firang for everything he did to make our trip to Ghana possible, for all the contacts he arranged, a place to live, and all the rest.

To my uncles Lauri and Reijo and their better halves Mirja and Liisa for welcoming us to Finland and making sure we were taken care of, housed, fed, had transportation... They were absolutely terrific all through the summer. Thanks too to the rest of the Suokonautio and Kosonen families for all your friendship and warmth, generosity and kindness.

To Catherine and her family in Estonia for putting us up. We were friends of friends and still you welcomed us.

To Tim, Martin, Leah, Gemma, Craig and family for helping us in our move from our house in Toronto. To my mom's neighbour Gwen for storing our stuff while we're away. To all of our friends who made sure we were sent off in style.

Oh! I'm out of time. More later then. But thanks again to everyone and again, Happy New Year! We love you.

Sunday, December 31, 2006

Friday, December 29, 2006

World-Walkers

Here is a rant/rap I wrote about the lessons of this journey back in London. Read fast for best results:

Walkin through the world with my white man’s eyes

Seeing pimps on vacation and priests telling lies

(on phony plantations under clear blue skies)

About crippled buffaloes on the brink of extinction

Chasing literate kids from dangerous depictions

Of million dollar bills and the myth of their freedom

Freedom ain’t free we told it takes bleedin

The White House literazis make blood literal

And they makin a crime outta bein a liberal

And the liberty from which kleptocracy was born

Is elusive as a high-horned unicorn

Amidst the ever present uniforms

Marching cross manufactured destiny

Trampling bleeding hearts like you and me

Hurling our bodies and pictures at the masses

With futures so dim they need coke-bottle glasses

Shouting our names the scariest of labels:

Jihad-lovin terrorists the other side of Abel

White House knows how to trample good ideas

Use the word terror and promise they’ll be freer

If we sacrifice now some kinda paradise awaits

So sacrifice liberty free speech and sell hate

The capitalist free-hand on the law’s long arm

Will slap every slave who tries to leave the farm

Or search for some meaning or true sense of home

Living in community instead of toiling alone

To feed the machine and climb the social ladder

On the heads of the helpless the rebels and the chatter

Of those who refuse the great compromise

Comfortably numb until a natural demise

These things I see from Helsinki to Osaka

Under leaders in suits from Thatcher to Mustafa

Nothin much changes in landscapes or time

Life is easy for the criminal mind

In the 3-piece suit at a microphoned table

With a Gucci watch and an Armoni label

While the beer-soaked escapists on the run

Ride third-class with a bottle and a shotgun

Mother Theresa hid in bubble-headed bliss

With her big good heart and a mailing list

But the war wages on with assaults on her poor

And anyone with money won’t fight anymore

Just push the button and your enemy is wiped

Send in the soldiers with chemicals and crackpipes

Hoping they survive civilian life

When state education spares their ass the knife

Or the gas or the gun or the garbage can

And slip them into slow death as a company man

But wait my white eyes see more than this

Like Mongolian herders following bliss

Falling all over in a fit of hard laughter

Eyes lit up with the knowledge of master

And the holder of more knowledge

Than is taught or learned in Ivey College

It’s the knowledge of the land and the secret of free

Knowing how to live beyond vicariously

Concretely over the land of generations

Sleeping under felt roofs until reincarnation

That bliss is so strong it beat the Soviets

Next to go down are the capitalists

Without trying to conquer but just to survive

And I also see other cultures being revived

Women in court speaking their own ancient language

With the gift of oration unpacking centuries of baggage

Before tin-eared judges too educated to understand

The ancient crimes of colonial man

And a sympathetic public that’s beginning to learn

About survival and revival and other ways to be

About the brain-washing propaganda machine

But I’ve also known way too much apathy

From the ones who should be down with what I seen

Thinking that by doing nothing they do no harm

While the fire eats paradise they turn up the charm

And waltz right through it untouched and unharmed

Sayin “please don’t hurt me look I’m unarmed”

How will all these sights in the world I behold

Look when untangled and when they unfold?

I know no better than so-called experts no TV

The real answer lies with you and with me

Walkin through the world with my white man’s eyes

Seeing pimps on vacation and priests telling lies

(on phony plantations under clear blue skies)

About crippled buffaloes on the brink of extinction

Chasing literate kids from dangerous depictions

Of million dollar bills and the myth of their freedom

Freedom ain’t free we told it takes bleedin

The White House literazis make blood literal

And they makin a crime outta bein a liberal

And the liberty from which kleptocracy was born

Is elusive as a high-horned unicorn

Amidst the ever present uniforms

Marching cross manufactured destiny

Trampling bleeding hearts like you and me

Hurling our bodies and pictures at the masses

With futures so dim they need coke-bottle glasses

Shouting our names the scariest of labels:

Jihad-lovin terrorists the other side of Abel

White House knows how to trample good ideas

Use the word terror and promise they’ll be freer

If we sacrifice now some kinda paradise awaits

So sacrifice liberty free speech and sell hate

The capitalist free-hand on the law’s long arm

Will slap every slave who tries to leave the farm

Or search for some meaning or true sense of home

Living in community instead of toiling alone

To feed the machine and climb the social ladder

On the heads of the helpless the rebels and the chatter

Of those who refuse the great compromise

Comfortably numb until a natural demise

These things I see from Helsinki to Osaka

Under leaders in suits from Thatcher to Mustafa

Nothin much changes in landscapes or time

Life is easy for the criminal mind

In the 3-piece suit at a microphoned table

With a Gucci watch and an Armoni label

While the beer-soaked escapists on the run

Ride third-class with a bottle and a shotgun

Mother Theresa hid in bubble-headed bliss

With her big good heart and a mailing list

But the war wages on with assaults on her poor

And anyone with money won’t fight anymore

Just push the button and your enemy is wiped

Send in the soldiers with chemicals and crackpipes

Hoping they survive civilian life

When state education spares their ass the knife

Or the gas or the gun or the garbage can

And slip them into slow death as a company man

But wait my white eyes see more than this

Like Mongolian herders following bliss

Falling all over in a fit of hard laughter

Eyes lit up with the knowledge of master

And the holder of more knowledge

Than is taught or learned in Ivey College

It’s the knowledge of the land and the secret of free

Knowing how to live beyond vicariously

Concretely over the land of generations

Sleeping under felt roofs until reincarnation

That bliss is so strong it beat the Soviets

Next to go down are the capitalists

Without trying to conquer but just to survive

And I also see other cultures being revived

Women in court speaking their own ancient language

With the gift of oration unpacking centuries of baggage

Before tin-eared judges too educated to understand

The ancient crimes of colonial man

And a sympathetic public that’s beginning to learn

About survival and revival and other ways to be

About the brain-washing propaganda machine

But I’ve also known way too much apathy

From the ones who should be down with what I seen

Thinking that by doing nothing they do no harm

While the fire eats paradise they turn up the charm

And waltz right through it untouched and unharmed

Sayin “please don’t hurt me look I’m unarmed”

How will all these sights in the world I behold

Look when untangled and when they unfold?

I know no better than so-called experts no TV

The real answer lies with you and with me

Saturday, December 23, 2006

Happy Holidays!

Happy Holidays, Seasons Greatings, Happy 2007, Peace Love and Hope to our friends, family, colleagues, and other readers of the Suokojamin World Tour!

We are headed to an Eco Village near the mighty Volta, near the Togo border in southern Ghana, for a relaxing (we hope) Christmas Day.

I leave you with a flashback to December 13, a Wednesday:

Mostly Wednesday was spent with Rich, an appropriately named 'Marketing Executive' who showed me where the government buildings are so that we could meet with a PR Man who was too busy and red-eyed hungry to see us. I had plenty of time to get to know this young man from Kumasi who hopes his job will get better. Selling advertising is a tough gig and I was given ample evidence last week. Frankie Boy replaced Rich on Thursday and he was a bit more talkative, wanting to know my likes and dislikes about Ghana - he really sympathized when I told him I love the friendliness and warmth and openness of people but hate how overwhelming those same great traits can be when they kick into oburoni (white person) induced overdrive. "They just are excited to meet a white person," he said. "But they need to respect your privacy and space." Frankie Boy is a smart guy, but that got us no where with the big men to whom we went begging, offering fluff pieces for a price and I realized I was wasting my time. But that day the paper ran the best piece I've done here, about village life and development, and I got a nice call of kudos from Rich that night. Frankie Boy promises to take us to a soccer game so all was not lost. Even Bossman himself was impressed by my early works. "I don't normally read the paper," he admitted. "But yours was very impressive." On my third and last day as an uninvited corporate guest I met Eddie, the only woman of the Mark Execs - she gave me a hard time until I confessed having had a poor sleep. The four of us were crammed into the company hatchback with our driver, who had just re-emerged from a week of AWOL. The conversation was fast and Twi and my head was filled with English-language worries abut the upcoming special edition, for which I'd met none of my assignments and would fail to do so if I didn't escape the clutches of a certain Marketing Manager with psychotic tendancies.

Fortunately it was Friday by then and nothing takes away the pain of a working week like sushi, ice cream, brownies, and real cappacino! You see it wasn't an ordinary Friday, it was the 3.5th anniversary of mine and Miia's fateful first date at the legendary El Mocambo, where Mick seduced Maggie back in the 60s or 70s or some other decade I don't remember. Emboldened and exhausted we embarked on another Accra weekend. Alas it was brownout night, and sleep was taunting in its evasions.

We are headed to an Eco Village near the mighty Volta, near the Togo border in southern Ghana, for a relaxing (we hope) Christmas Day.

I leave you with a flashback to December 13, a Wednesday:

Mostly Wednesday was spent with Rich, an appropriately named 'Marketing Executive' who showed me where the government buildings are so that we could meet with a PR Man who was too busy and red-eyed hungry to see us. I had plenty of time to get to know this young man from Kumasi who hopes his job will get better. Selling advertising is a tough gig and I was given ample evidence last week. Frankie Boy replaced Rich on Thursday and he was a bit more talkative, wanting to know my likes and dislikes about Ghana - he really sympathized when I told him I love the friendliness and warmth and openness of people but hate how overwhelming those same great traits can be when they kick into oburoni (white person) induced overdrive. "They just are excited to meet a white person," he said. "But they need to respect your privacy and space." Frankie Boy is a smart guy, but that got us no where with the big men to whom we went begging, offering fluff pieces for a price and I realized I was wasting my time. But that day the paper ran the best piece I've done here, about village life and development, and I got a nice call of kudos from Rich that night. Frankie Boy promises to take us to a soccer game so all was not lost. Even Bossman himself was impressed by my early works. "I don't normally read the paper," he admitted. "But yours was very impressive." On my third and last day as an uninvited corporate guest I met Eddie, the only woman of the Mark Execs - she gave me a hard time until I confessed having had a poor sleep. The four of us were crammed into the company hatchback with our driver, who had just re-emerged from a week of AWOL. The conversation was fast and Twi and my head was filled with English-language worries abut the upcoming special edition, for which I'd met none of my assignments and would fail to do so if I didn't escape the clutches of a certain Marketing Manager with psychotic tendancies.

Fortunately it was Friday by then and nothing takes away the pain of a working week like sushi, ice cream, brownies, and real cappacino! You see it wasn't an ordinary Friday, it was the 3.5th anniversary of mine and Miia's fateful first date at the legendary El Mocambo, where Mick seduced Maggie back in the 60s or 70s or some other decade I don't remember. Emboldened and exhausted we embarked on another Accra weekend. Alas it was brownout night, and sleep was taunting in its evasions.

More of other people's pictures

Here is Makola market, the main and most central market in Accra. Before Christmas it is really the closest thing to utter chaos I've ever witnessed in my life. And yet somehow completely ordered.

A pictures of Ghanaian dancers similar to the ones I saw the other night.

And these are some traditional Ghanaian fabrics. Colourful and fun. The geometric designs and the weaving is a tradition from the North (I believe) and is called Kente cloth.

Just some pics to give you an idea of life here.

Attorney General pukes all over victims of tyrrany

Well, my interview with the Attorney General became the cover story for our special Christmas edition, which seems a pretty big deal. He was one shifty man with a serious attitude problem, but thanks to his aide I managed to get a decent scoop:

http://www.thestatesmanonline.com/pages/news_detail.php?newsid=1827§ion=1

Chris

http://www.thestatesmanonline.com/pages/news_detail.php?newsid=1827§ion=1

Chris

Friday, December 22, 2006

Other People's Pictures

Here is a woman walking down a dirt road in Ghana. Much like the road to our house. Note how red the soil is.

A Ghanaian taxi. They vary greatly in terms of state of disrepair and you always negotiate your price before going. Many interesting cab drivers we've had.

The insanity is Kaneshie Market, a shotr bus ride from our house (depending on traffic). It's a market and trotro (bus) station rolled into one. You need all your faculties to navigate nevermind shop.

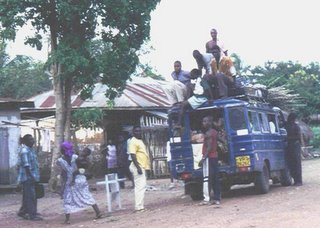

And the last is a blue trotro. People do not ride on top but cargo is loaded on top and in the back. Generally you get 18 passengers or so, depending on the size and how it's been retrofitted. From our house to the main trotro station we go to, the fare is 3,000 cedis or 36 cents. From Accra to the town of Ho, a 2.5-3 hour trip to the capital of the Volta region, the fare is 30,000 cedis = $3.60.

Yes, these are other people's pictures but thought they might help you get a picture of what things are like here.

Looking the Other Way

Chris says, "Let's resolve to have a good day today, OK?"

"OK."

And it was.

21/12/2006 - one month in Ghana

Share taxi with Chris. I get off at Circle station (Circle is short for Kwame Nkrumah Traffic Circle - one of the major traffic hubs in Accra). Traffic is killer before Christmas. Lots of standing still.

Photocopy a little shop all the paperwork for the university, incl. transcripts, resume, forms. The power connection comes and goes and the guy working at the store presses copy when the lights stop flickering.

Bus to University. Really nice woman beside me and we chat about this and that.

Drop off the paperwork. The opposition party was having it's leadership conference and the campus was full of people in colourful outfits, small parades, dancing, music. Alive.

Bus back to Circle. Buy fish pies from street vendor, a woman who doesn't speak English i.e. has not gone to school. She is warm and seems happy to communicate with me anyway, however we can.

Bus to Laterbiorkoshie and walk to the office of People's Dialogue. Hang out with Mabel the receptionist/accountant and chat. She is liking me more all the time. Me too her. Chat with Farouk and Lukman about plans for 2007 - I'd like to be doing more hands on stuff. Yes, we'll talk about it. I laugh that they should hire me and Lukman says, with great earnestness, yes! We'd love to hire you because then we could use you even more, have you here more. I'm flattered. When I leave, Mabel gives me a huge hug. Feels so good to be hugged. We've been strangers to everyone for a long time and never really feel close enough to anyone, it seems, to be hugged. I like it and feel... humbled. A friend.

I grab a cab back to Dansoman and it's a cabbie I've had before. We start to talk about politics and about the NDC candidate race. He says he's not about parties and votes for whoever makes the best promises. He starts to complain about the current party, that they haven't done enough, that crime has become a big problem. His cell phone was stolen. "Before," he says, "when the previous party was in power, if you were caught stealing, you would be killed. Now you get a lawyer!" "What we need," he says, "is more people's justice. Like, just recently a 22-yr-old guy was caught trying to steal the contents of a car in Dansoman. The people killed him. They beat him to death." "Were you there?" I ask. "Yes!" he replies, "I was there. And I think it's good he was killed. Too bad he was so young but now others know." Mm-hmmm. "Well," I say, "I think stealing is wrong. It also affects a whole community because you start to be afraid in your own home. BUT, I think is killing is even more wrong." Really, what more could I say?

I do an hour of internet and buy some canned mackerel and walk home. On my way, I stop by at a small shop stall that has beautiful batiks and fabrics. The seamstress takes my measurements and will have a dress ready for me in a week or so. Made to measure dress from hand dyed fabric: CDN$10. Can't be beat. I'm excited for my new dress.

As I am walking, I hear the familiar sound of drums in the park at the top of our street. It's a nightly thing. But somehow, I've never really HEARD it before. It's a warm early evening, already dark outside, and here I am in Africa and I can hear drums and singing. I approach two friendly looking youth on the street and ask, "What is that drumming?" "It's a group." "At the school." "No, at the culture centre." "Culture centre?" "Yes," says the young man, "I'd like to show you. Would you like to come?" "Yes, please. Let's go." He leads me down a path to a small centre at the back where there are not only drummer but eight dancers. They are dancing unbelievably fast. Indescribably fast. And still in sync. I stand mouth agape and watch. Amazing. Truly amazing. The dancers seem a little shy that I'm watching but they are so talented, so fit, so strong. They speak Ga between them, a smaller of the tribes of Ghana (the Ashante being the biggest). What fun indeed. And everyone was so nice.

Eventually I go home, make spaghetti with tomato sauce and fish. I shower and read in bed. Chris is working late for the special edition of the newspaper coming out the next day and his is the cover story. Eventually he comes home, we spend time together as he has his dinner, and tell our tales about the day.

Yes, we both had a good day. Let them all be so!

"OK."

And it was.

21/12/2006 - one month in Ghana

Share taxi with Chris. I get off at Circle station (Circle is short for Kwame Nkrumah Traffic Circle - one of the major traffic hubs in Accra). Traffic is killer before Christmas. Lots of standing still.

Photocopy a little shop all the paperwork for the university, incl. transcripts, resume, forms. The power connection comes and goes and the guy working at the store presses copy when the lights stop flickering.

Bus to University. Really nice woman beside me and we chat about this and that.

Drop off the paperwork. The opposition party was having it's leadership conference and the campus was full of people in colourful outfits, small parades, dancing, music. Alive.

Bus back to Circle. Buy fish pies from street vendor, a woman who doesn't speak English i.e. has not gone to school. She is warm and seems happy to communicate with me anyway, however we can.

Bus to Laterbiorkoshie and walk to the office of People's Dialogue. Hang out with Mabel the receptionist/accountant and chat. She is liking me more all the time. Me too her. Chat with Farouk and Lukman about plans for 2007 - I'd like to be doing more hands on stuff. Yes, we'll talk about it. I laugh that they should hire me and Lukman says, with great earnestness, yes! We'd love to hire you because then we could use you even more, have you here more. I'm flattered. When I leave, Mabel gives me a huge hug. Feels so good to be hugged. We've been strangers to everyone for a long time and never really feel close enough to anyone, it seems, to be hugged. I like it and feel... humbled. A friend.

I grab a cab back to Dansoman and it's a cabbie I've had before. We start to talk about politics and about the NDC candidate race. He says he's not about parties and votes for whoever makes the best promises. He starts to complain about the current party, that they haven't done enough, that crime has become a big problem. His cell phone was stolen. "Before," he says, "when the previous party was in power, if you were caught stealing, you would be killed. Now you get a lawyer!" "What we need," he says, "is more people's justice. Like, just recently a 22-yr-old guy was caught trying to steal the contents of a car in Dansoman. The people killed him. They beat him to death." "Were you there?" I ask. "Yes!" he replies, "I was there. And I think it's good he was killed. Too bad he was so young but now others know." Mm-hmmm. "Well," I say, "I think stealing is wrong. It also affects a whole community because you start to be afraid in your own home. BUT, I think is killing is even more wrong." Really, what more could I say?

I do an hour of internet and buy some canned mackerel and walk home. On my way, I stop by at a small shop stall that has beautiful batiks and fabrics. The seamstress takes my measurements and will have a dress ready for me in a week or so. Made to measure dress from hand dyed fabric: CDN$10. Can't be beat. I'm excited for my new dress.

As I am walking, I hear the familiar sound of drums in the park at the top of our street. It's a nightly thing. But somehow, I've never really HEARD it before. It's a warm early evening, already dark outside, and here I am in Africa and I can hear drums and singing. I approach two friendly looking youth on the street and ask, "What is that drumming?" "It's a group." "At the school." "No, at the culture centre." "Culture centre?" "Yes," says the young man, "I'd like to show you. Would you like to come?" "Yes, please. Let's go." He leads me down a path to a small centre at the back where there are not only drummer but eight dancers. They are dancing unbelievably fast. Indescribably fast. And still in sync. I stand mouth agape and watch. Amazing. Truly amazing. The dancers seem a little shy that I'm watching but they are so talented, so fit, so strong. They speak Ga between them, a smaller of the tribes of Ghana (the Ashante being the biggest). What fun indeed. And everyone was so nice.

Eventually I go home, make spaghetti with tomato sauce and fish. I shower and read in bed. Chris is working late for the special edition of the newspaper coming out the next day and his is the cover story. Eventually he comes home, we spend time together as he has his dinner, and tell our tales about the day.

Yes, we both had a good day. Let them all be so!

Thursday, December 21, 2006

Wednesday, December 20, 2006

An International Human Rights Day at the Beach

On International Day for Human Rights, a Sunday, we met Henry at La Beach. The entrance fee is 20,000 cedis ($2.50) and we didn’t realize that Henry would need his fee covered by us. He also mentioned that someone had tried to take something from him illegally but it was one of those conversations where meaning is lost in translation and further questioning takes you nowhere. When I got up to meet Henry at the front gate a Nigerian boy named Douglas took his chance to sit down with Miia. When I returned he invited us both to his house and asked for my phone number, which people do a lot here, and in some cases (including this one) they end up calling you daily and nightly. Douglas left us for a while before returning with his elder brother, Wisdom, who had a serious case of bigmanitis, which was further agitated by inebriation. He took great delight in haggling with a mask vendor in front of us and insisting he had no more money to pay, before pulling out a giant wad of cash with his rolex hand to make his purchase. He warned us to be careful who we are friendly with and strutted off looking for lesser peacocks to recruit or subdue. Before the day was out we saw Wisdom involved in a near fistfight with Foolishness.

In Douglas’s case the phone calls came during free call hours, after 11 pm and before 7 am, and they started the same day I gave him the number. Eventually Miia put a stop to it without even offering any excuses; I was humbled by her assertiveness. It’s a shame that the first Nigerians we met here turned out to be slimy scammers because that is the stereotype many Ghanaians have of them. Fortunately we will have ample opportunity to meet other Nigerians who deflate the stereotypes.

Firsts

Have you ever wondered who buys all those weight-loss gimmicks you see on television? Wonder no more: it is the Captain. He even has the vibrating belt, over which his money gut sweats all morning while he watches the news, before doing walking laps of the house with Sarah, and several minutes on the Nordic track. After observing this spectacle over instant coffee we hopped in a cab with a philosophical hopeless romantic driver who listened to nothing but Brian Adams and was thrilled to learn of the superstar’s Canadian roots. “I have all his cassettes, except the ones that haven’t come here yet – they always take so long to reach Ghana.” He was egalitarian on the issue of race. “Most people see you white they’ll double or triple the price for you,” he said. “But me, I charge the same for white, black, yellow, whatever.” For his equal rate he drove us all the way to the dentist, where my tooth was granted a temporary stay of execution and given daily saltwater swimming privileges.

I wish pickpockets were as egalitarian as that driver, but I’m pretty sure I was targeted for easy pickins. We were rushed into a trotro by an overenthusiastic mate (the guy who takes the money and helps the driver). I sat in back and Miia went up front. The guy in front of me handed back the change to the guy beside me, and somehow it got dropped. I helped to pick it up and he dropped it again; I helped again and he dropped it again. “Maybe you can get it yourself,” I said. It was then that I realized my cell phone was halfway out from my Velcro pocket. I jammed it back in and shoved myself away from him, but I was so scared to make a false accusation I let it drop and when he moved up to the seat in front of me I figured the phone must have just slid part-way out, as can happen with shallow pockets in a crowded vehicle.

When I got out of the vehicle, the same guy, who wore a full-length turquoise African print, let me go by him, which is in itself unusual. His accomplice, the original change dropper, had also moved up a row and when he got out he dropped the aisle chair (which can swing up to let people out) down in front of me so I had to stop and pick it up again. It was then I felt Mr. Turquoise’s hands all over me like an overeager teenage on a first date. I slapped his hand away and shouted “get your hands off me!” He climbed down from the bus after me and I glared but said nothing. I realized, only after he’d left the scene, that he had succeeded in nabbing about 30,000 (maybe $4) from me. It’s not a big loss, but I hate being targeted like that, double-teamed, mildly invaded.

Miia took it even harder than I did and went hunting for the guy. We found a turquoise-clad man nearby and I think it was him, but he denied having been on the bus with me and told Miia she was beautiful. I decided it better to just leave it be than confront possibly the wrong guy over 4 bucks. We walked through the market (where several men have tried and failed to pocket my possessions) and grabbed another trotro homeward and thanked the gods for the survival of my tooth against all odds.

That night I tried banku (fermented corn and cassava beat into a gooey paste, like fufu but fermented) for the first time, and was surprised to find it more palatable than fufu despite the fermentation.

In Douglas’s case the phone calls came during free call hours, after 11 pm and before 7 am, and they started the same day I gave him the number. Eventually Miia put a stop to it without even offering any excuses; I was humbled by her assertiveness. It’s a shame that the first Nigerians we met here turned out to be slimy scammers because that is the stereotype many Ghanaians have of them. Fortunately we will have ample opportunity to meet other Nigerians who deflate the stereotypes.

Firsts

Have you ever wondered who buys all those weight-loss gimmicks you see on television? Wonder no more: it is the Captain. He even has the vibrating belt, over which his money gut sweats all morning while he watches the news, before doing walking laps of the house with Sarah, and several minutes on the Nordic track. After observing this spectacle over instant coffee we hopped in a cab with a philosophical hopeless romantic driver who listened to nothing but Brian Adams and was thrilled to learn of the superstar’s Canadian roots. “I have all his cassettes, except the ones that haven’t come here yet – they always take so long to reach Ghana.” He was egalitarian on the issue of race. “Most people see you white they’ll double or triple the price for you,” he said. “But me, I charge the same for white, black, yellow, whatever.” For his equal rate he drove us all the way to the dentist, where my tooth was granted a temporary stay of execution and given daily saltwater swimming privileges.

I wish pickpockets were as egalitarian as that driver, but I’m pretty sure I was targeted for easy pickins. We were rushed into a trotro by an overenthusiastic mate (the guy who takes the money and helps the driver). I sat in back and Miia went up front. The guy in front of me handed back the change to the guy beside me, and somehow it got dropped. I helped to pick it up and he dropped it again; I helped again and he dropped it again. “Maybe you can get it yourself,” I said. It was then that I realized my cell phone was halfway out from my Velcro pocket. I jammed it back in and shoved myself away from him, but I was so scared to make a false accusation I let it drop and when he moved up to the seat in front of me I figured the phone must have just slid part-way out, as can happen with shallow pockets in a crowded vehicle.

When I got out of the vehicle, the same guy, who wore a full-length turquoise African print, let me go by him, which is in itself unusual. His accomplice, the original change dropper, had also moved up a row and when he got out he dropped the aisle chair (which can swing up to let people out) down in front of me so I had to stop and pick it up again. It was then I felt Mr. Turquoise’s hands all over me like an overeager teenage on a first date. I slapped his hand away and shouted “get your hands off me!” He climbed down from the bus after me and I glared but said nothing. I realized, only after he’d left the scene, that he had succeeded in nabbing about 30,000 (maybe $4) from me. It’s not a big loss, but I hate being targeted like that, double-teamed, mildly invaded.

Miia took it even harder than I did and went hunting for the guy. We found a turquoise-clad man nearby and I think it was him, but he denied having been on the bus with me and told Miia she was beautiful. I decided it better to just leave it be than confront possibly the wrong guy over 4 bucks. We walked through the market (where several men have tried and failed to pocket my possessions) and grabbed another trotro homeward and thanked the gods for the survival of my tooth against all odds.

That night I tried banku (fermented corn and cassava beat into a gooey paste, like fufu but fermented) for the first time, and was surprised to find it more palatable than fufu despite the fermentation.

Return to the Village

Our return to Ayirebi village was less eventful and less comfortable than our first trip. We landed first in a bus station insane asylum where the inmates swarmed us like a last meal offering friendship, transportation and merchandise all at a fair price. We headed right over the wall and landed at the next station over, where we were rescued by David and his brother-in-law, a professional getaway driver surrounded by hitman serenity. “I’m so happy you’re here,” David told us. “We’re so bored in the village! And I miss my boy. How’s he doing?” Sim is actually performing much more regularly under the watchful eye of Dacosta, who notes wistfully that corporal punishment is normal in Ghana.

We made a few stops along the way to the village, including a visit to a district assembly executive, who told us about the newest craze: cultural tourism. “The white people we know like to stay in big hotels,” he told us, but he had learned of another breed that apparently enjoys meeting people and learning about the place their in. When he learned that I write for the paper he jumped double-footed into the conversation and tossed a card and a special report my way.

We were put up in the spare house of a local doctor which was visibly clean but smelled of bat urine, where we slept on a comfortable mattress under two full-blast ceiling fans to ensure our full attention at the morning ceremony. The turnout was Friday low but some local politicians and media made the day and quoted our near-impromptu speeches verbatim. The Chief thanked us for single-handedly saving the village and we reiterated that it was but a small donation to a hardy and innovative group of people who had survived thousands of years without us. There was the usual talk of us starting an NGO and our usual efforts to diffuse such misplaced time-bombs. Our speeches were punctuated by spontaneous outbursts of cheers from the crown, especially when Miia said that girls need better access to school – at the moment they make up less than 40% of the senior secondary school.

After the ceremony I wanted to visit the new school feeding program where every primary student gets one square meal from the government; it’s a means to encourage attendance and improve health, and comes complete with de-worming kits and monthly weigh-ins to track growth. We brought along our own entourage in the form of David’s sister and his nephews, who had not forgotten our last visit and spent hours hanging about our windows peeking in at us, and loved holding our hands. The Sister wanted to know if having a pen-pal in Canada would improve her chances of immigrating there.

The teachers raved about the program saying attendance was soaring, and the kids tore through giant bowls of food. I interviewed a couple teachers and the lunch-lady on behalf of the paper while Miia did recognizance work via informal conversations and snapshots of the hungry future of the village. “Make sure you mention my name in the article,” said the Sister, a teacher herself but at a different school.

The only detractor from the program we found was our host, Dr. Bigman, who paid us a visit that evening as his minions ran in to build us a new bed. “I have a mattress that is Canadian-sized,” he told us. “But it needs a frame.” Fortunately the bed-frame was not really ready because the Canadian-sized mattress was filthy and we preferred the Ghana size, which is a double. The good doctor, who used to be leader of the opposition, a splinter group from the former military dictator turned international speech giver Flight Lieutenant Jerry J. Rawlings, explained to us that he is a rich man in terms of assets, even if other Ghanaian doctors who stayed in the west make more money. “I have six children and three houses,” he told us. “My friend in the UK has only one house and one child, a daughter.” Dr. Bigman felt that the school feeding program encourages children to go to school only to have them leave without an education, and that educating farmers is dangerous anyway because next thing you know they don’t want to farm anymore. “What they need is to be told to farm a small piece of land as hard as they can, like in the Soviet Union,” where he himself had been educated. It was the first time I’d ever heard someone use the Soviet Union as a good example of agricultural management.

Our ongoing party was joined by a Mr. Sleezmo, a long-time beat writer from the Daily Graphic, who informed me, several times, that the Daily Graphic is the biggest paper in the country, reaching 200,000 readers (I had heard 50,000 so maybe let’s call it an even hundred). He wanted to know how much our donation was until David intervened saying “don’t worry about the amount.” The writer wanted to know if we’d start an NGO and where in the world we had traveled (and also how to spell the names of those countries).

“Come to us you can write every day,” he told me, refusing my request for a business card. When I ran into him the next day he did make a point of showing my his name as the writer of a piece in the paper and reminded me of the circulation figures; whether he was trying to win me over to the graphic or rub it in that I worked in the minor leagues was unclear. I do wonder what it would be like to write for a state-run and controlled newspaper that focuses on crime stories and has a large circulation.

In time we finally excused ourselves from our gracious host and paid a late-night visit to the Chief, both to pay our respects and interview him for the paper. He obliged on both accounts and also humbly asked us for money to help him publish his book about the chieftancy system. We capped the day with a discussion with David about corruption, culture shock, and the tendency of some people to get a little and ask for more more more.

The next morning we met with the youngest district assembly member in the region and a village elder to hand over the 500,000 cedi (about $60) donation we promised and had a great antidote of a conversation about how education and agriculture are not mutually exclusive. He young DA member had great energy and optimism and told us that he ran for office because he wanted to help his elders bring positive developments to his village.

It was then that we tried fufu, cassava and corn pounded into a gooey pasty doughy kind of stuff that you dip in peanut sauce with fish – it’s as tasty as it sounds. David and Hannah took us out for lunch in the nearby town before we headed back to Accra. It is a delicacy that Ghanaians take very seriously: I read an account of inmates who, denied their fufu, pounded their cassava with their infected feet on a dirty floor to make it for themselves.

We made a few stops along the way to the village, including a visit to a district assembly executive, who told us about the newest craze: cultural tourism. “The white people we know like to stay in big hotels,” he told us, but he had learned of another breed that apparently enjoys meeting people and learning about the place their in. When he learned that I write for the paper he jumped double-footed into the conversation and tossed a card and a special report my way.

We were put up in the spare house of a local doctor which was visibly clean but smelled of bat urine, where we slept on a comfortable mattress under two full-blast ceiling fans to ensure our full attention at the morning ceremony. The turnout was Friday low but some local politicians and media made the day and quoted our near-impromptu speeches verbatim. The Chief thanked us for single-handedly saving the village and we reiterated that it was but a small donation to a hardy and innovative group of people who had survived thousands of years without us. There was the usual talk of us starting an NGO and our usual efforts to diffuse such misplaced time-bombs. Our speeches were punctuated by spontaneous outbursts of cheers from the crown, especially when Miia said that girls need better access to school – at the moment they make up less than 40% of the senior secondary school.

After the ceremony I wanted to visit the new school feeding program where every primary student gets one square meal from the government; it’s a means to encourage attendance and improve health, and comes complete with de-worming kits and monthly weigh-ins to track growth. We brought along our own entourage in the form of David’s sister and his nephews, who had not forgotten our last visit and spent hours hanging about our windows peeking in at us, and loved holding our hands. The Sister wanted to know if having a pen-pal in Canada would improve her chances of immigrating there.

The teachers raved about the program saying attendance was soaring, and the kids tore through giant bowls of food. I interviewed a couple teachers and the lunch-lady on behalf of the paper while Miia did recognizance work via informal conversations and snapshots of the hungry future of the village. “Make sure you mention my name in the article,” said the Sister, a teacher herself but at a different school.

The only detractor from the program we found was our host, Dr. Bigman, who paid us a visit that evening as his minions ran in to build us a new bed. “I have a mattress that is Canadian-sized,” he told us. “But it needs a frame.” Fortunately the bed-frame was not really ready because the Canadian-sized mattress was filthy and we preferred the Ghana size, which is a double. The good doctor, who used to be leader of the opposition, a splinter group from the former military dictator turned international speech giver Flight Lieutenant Jerry J. Rawlings, explained to us that he is a rich man in terms of assets, even if other Ghanaian doctors who stayed in the west make more money. “I have six children and three houses,” he told us. “My friend in the UK has only one house and one child, a daughter.” Dr. Bigman felt that the school feeding program encourages children to go to school only to have them leave without an education, and that educating farmers is dangerous anyway because next thing you know they don’t want to farm anymore. “What they need is to be told to farm a small piece of land as hard as they can, like in the Soviet Union,” where he himself had been educated. It was the first time I’d ever heard someone use the Soviet Union as a good example of agricultural management.

Our ongoing party was joined by a Mr. Sleezmo, a long-time beat writer from the Daily Graphic, who informed me, several times, that the Daily Graphic is the biggest paper in the country, reaching 200,000 readers (I had heard 50,000 so maybe let’s call it an even hundred). He wanted to know how much our donation was until David intervened saying “don’t worry about the amount.” The writer wanted to know if we’d start an NGO and where in the world we had traveled (and also how to spell the names of those countries).

“Come to us you can write every day,” he told me, refusing my request for a business card. When I ran into him the next day he did make a point of showing my his name as the writer of a piece in the paper and reminded me of the circulation figures; whether he was trying to win me over to the graphic or rub it in that I worked in the minor leagues was unclear. I do wonder what it would be like to write for a state-run and controlled newspaper that focuses on crime stories and has a large circulation.

In time we finally excused ourselves from our gracious host and paid a late-night visit to the Chief, both to pay our respects and interview him for the paper. He obliged on both accounts and also humbly asked us for money to help him publish his book about the chieftancy system. We capped the day with a discussion with David about corruption, culture shock, and the tendency of some people to get a little and ask for more more more.

The next morning we met with the youngest district assembly member in the region and a village elder to hand over the 500,000 cedi (about $60) donation we promised and had a great antidote of a conversation about how education and agriculture are not mutually exclusive. He young DA member had great energy and optimism and told us that he ran for office because he wanted to help his elders bring positive developments to his village.

It was then that we tried fufu, cassava and corn pounded into a gooey pasty doughy kind of stuff that you dip in peanut sauce with fish – it’s as tasty as it sounds. David and Hannah took us out for lunch in the nearby town before we headed back to Accra. It is a delicacy that Ghanaians take very seriously: I read an account of inmates who, denied their fufu, pounded their cassava with their infected feet on a dirty floor to make it for themselves.

Monday, December 18, 2006

Wonderful Mongolian Family

Sunday, December 17, 2006

Many Things

Sunday

On Sunday we awoke to the 5 am drum parade circulating around our door, which was good preparation for a four-hour church service with three offerings, during which the preacher preached about how we are no different than madness with our clothes unfit for public consumption. “If he treated his first wife that way he’ll treat you the same; don’t believe his smooth talk!” he admonished us as we sweated in our tight white traditional funeral wear, up front and centre under the light of the videographer, projected onto the big screen TV. During the collections he reminded the congregation that believers give generously.

Patrick made no qualms about explaining the service. “All they want is money,” he said. “People here living hand to mouth in abject poverty and they have three offerings! Keep us in church for four hours.” He’s a believer but he has his limits and he doesn’t understand how so many different races could all be descendant from Adam and Eve either.

We relieved our post-church headaches in a dance with David’s nephews and nieces, Bernard, Evans and Albert and the twin girls both named Albena, with whom we exchanged moves and drew a crowd until David’s drunken cousin gave us the old pinch, a hard one. We asked David to give him a little talk, which David did very publicly before sending him home for the night, leaving us to sheepishly sip our cokes in the courtyard, where the kids raised Cain with paper airplanes and cranes made by Miia. Bernard sat on my lap and I snuck him sips of my coke (such a delicacy is not normally wasted on children). When I told him to share the remainder with his friends a near brawl ensued, and somehow David’s son Sim was at the epicentre. “That boy is mad,” said Bernard. Sim’s culture shock seemed to be agitating his ADD and none of the locals’ efforts to teach him good Ghanaian manners seemed to help much. A few piggyback rides distracted the kids from their problems.

We ate dinner with Dacosta, who loves the village food because it is so much fresher than in the city he now calls home.

Producing and Exporting Countries

After all the official things we had the chance to linger in bed and talk politics to the backbeat of the usual Christian music from the electronics store. “Why don’t all the cocoa, coffee and sugar producers create a CCSPEC and take Nestle over, drive up the prices on our non-petroleum addictions and make more money for the farmers.” That kind of nonsense. “Funny how cell phones make sense here and have brought people together, but they still exclude rural people who don’t have money and can’t get signals.”

Eventually we made way to see the Chief, passing a hoard of pre-schoolers on the way who made up a song: “white man give me money.” Their voices were beautiful until someone explained what the words meant.

We discussed the latest of David’s brain children with the Chief: he wants to start an organization and build a community centre, and we agreed to chip in a few dollars. Somehow this small gesture led to the Chief offering to make us Sub-Chief and Queen Mother, an offer that came with a lesson in the Chieftancy system (a subject on which the Chief has written a yet unpublished book): they must maintain political neutrality with no partisan affiliation, yet be judge jury mayor and planner for their village. The Chief is accountable to the village elders, who chose him and can remove him any time – unlikely in this case because he has served as Chief for 40 years. Society is patralineal with tremendous importance placed on clan or extended family. No one is without a parent: David has just inherited his father’s sister as his new mother. Age cannot prevent parentage; in some cases your father’s brothers little boy is considered your father. This way people are cared for all their lives; they are never alone and, from the North American point of view, they never have privacy.

By the time we left the Chief we had somehow committed ourselves to return for a ceremony in honour of our small gift toward the community centre. We thanked him for his lessons and his time and Henry took us straight to the senior secondary school, where the security guard had more time to kill than intruders and had landscaped himself a rock, sand, grass and shrub garden, which he took great delight in showing us. When we found the principal he was quick to announce, “We are a deprived school with many needs: lab equipment, books, uniforms.” The school receives little government support and runs mostly from school fees, which prevent many of the villagers from gaining an education beyond primary school. My internal calculator told me that the money required to educate every child in the village would be a few tens of thousands of dollars a year, and I wished I had that much to give or that I could devise an effective educational system that doesn’t require books, equipment, uniforms or buildings, only teachers. But I’m much better at criticizing pedagogy than inventing it.

The mild depression induced by the principal was quickly cured by the students whose classes we visited briefly. They were full of enthusiasm for life’s possibilities and asked us questions like ‘are you married?’ and ‘do you use chemistry in your life?’ We promised to return with addresses for Canadian universities so they can send away for application packages.

We left when classes were dismissed and later Dacosta accompanied to town on a full-sized bus like you find in rich countries, with a raised section in the back that gave us a clear view of the madness of the countryside roads. With fresh memories of the accident we held tightly to the seat in front of us and consoled ourselves with thoughts of the great mass of the vehicle and the unlikelihood of it crumpling around us in an accident. We made it safely to town but struck out on arrival: no sunscreen and no power. We checked our email at a café with a generator and took a 90 miles an hour taxi back to the village, holding hands. There was a dispute over the fee in which the driver refused our money unless more was added. Dacosta won the argument, as is his way.

We decided that night, based on village life, that I’m stronger at handling resource scarcity and Miia is stronger at handling the intense scrutiny and attention of an entire society. As a cab driver later pointed out to us, “no one is so strong in a car accident.”

Unearned Expertise

On our way to catch our ride back to Accra we met Ahmed, who had been our translator with the Chief (who speaks perfect English but tradition demands a translator). He told me that he started a local environmental group called Evergreen and he’d love my advice, something I felt utterly unqualified to offer, yet would have loved to learn more about. We agreed to talk in more detail on my return.

We got a ride with David’s old ‘mentor’ The Captain, who captains an Iranian merchant ship and runs several businesses (internet café, taxi service, farms, etc.). A few minutes down the road we heard a tearing noise and shrapnel started raining in through the open back window on Miia. She ducked into me in the middle seat and was luckily unharmed. It turned out to be nothing worse than a shredded tire but on the heals of the accident it had our hearts racing.

David and Patrick were just a few minutes behind us in a Tro-Tro (minivan bus) and were able to get us another ride into the nearest town, from where we we took a Tro-Tro all the way to Accra, which was thankfully uneventful.

We made it back just in time for the launch of CofA, College for Ama (a Saturday born woman likely to be studious by nature).

Two of the three founders gave speeches mentioning the importance of their fathers, who were visionary enough to insist on the education of their daughters in villages where female education is often seen as wasteful. Helen told of how her father used to make her take our library books and tell him what she learned before returning them. Professor Nana Apt added a story about how she returned to her home village to seek out her four former female classmates. One was dead, one in a mental institution, one old before her time, and the last led a life riddled with problems. Only she had been able to complete school and have more options, she told us. She wanted her program to help other girls have options.

There were supporters there all the way from the UK and America, one of whom read a beautiful poem about the birth of her daughter and her contemplation about whether the men in her life understood the importance of supporting the girl through her life. Another woman had started a similar program in Oregon and was raising money to give American girls the chance to travel to Ghana and meet and learn with their counterparts and peers here. She finished by giving a small check that her students had raised for CofA, but her speech felt sort of like a sales pitch. There were many questions, the most potent of which was “why are you focusing only on strong female students; what about weak students, shouldn’t they too receive support in their education?”

After the formalities we met Theresa, who works with an HIV education group in northern Ghana and invited us to come see their work, and Matt from Seattle who raises money for the private university and has lived her long enough to learn some Twi. It was he who informed us of the weekly pickup basketball games, though we have yet to see him there.

Outside attempting to sate our daylong hunger with crackers and fanta Jima found us; he had been sent to take us back to Lydia’s. We begged him to stop at a Chop so we could eat some faster than average cheap and tasty food.

New NGOs

Despite receiving several requests to start an NGO here we remain firm in our position that we are better suited to get involved with the work that is already happening here. We have neither the time, the money, nor the expertise to identify unfulfilled needs and try to fill them with an organization that we would have to abandon when we go home anyway.

Lydia on the other hand does have the expertise to see what is needed here, and she wants to start an organization to take care of the many orphans who end up on the streets of Accra, before they get there. It’s difficult for her though because she has to take care of the world’s strongest baby by herself. “This child is ruining my life,” she jokes. “I just need find a buyer for him.” Isaac usually responds by finding something to pull into pieces, preferably a piece of electronics or jewelry.

We gave Lydia some advice on her NGO: “write a business plan, explain how you will monitor results, get a board of committed, well connected and preferably rich people who can offer time and skills.”

She looked at us kind of blankly and said, “Nobody in Ghana helps like that.” Aside from the year of mandatory volunteer work Ghanaians do not have that culture of volunteerism, maybe because money is scarce or maybe because government here actually puts what resources it can into education, health and poverty reduction.

I tried to excuse our big talk and encourage her to start small, who knows where it could go. I hope she will give it a go, but even small scale it’s a big undertaking. We let it go and showed her our travel pictures and she showed us family photos on her laptop. Then we went shopping.

Market Madness

We made major investments in Ghanaian knowledge at the university bookshop – what a treasure chest! Then in the insanity of Makolah Market I was mobbed by five purveyors of pants, each frantically searching to show me a size 32, light coloured, cotton pair, except they showed me everything but. Only the sixth seller succeeded. Lydia bought a few things too, one of which was a tea towel she didn’t need. “I bought it because she was pregnant and has been walking in the sun for hours,” she told us.

A beautiful day was marred by marginally a corrupt cop, who pulled us over when Jima allegedly ran a red light on a left turn. He hopped into Jima’s lap and asked for a license, which was not produced. Lydia took the wheel and the cop informed her they were under arrest. They argued in Twi until we reached the police station, when Lydia finally relented to the 20,000 cedi ($2.50) bribe. On the way home she saw a cripple begging on the road; he was from her hometown so she put the window down to chat and gave him 10,000.

Two Tips for Life in Accra

When walking through the market at night watching vendors sell Nike and Nokia by candlelight, stuff all valuables out of reach and out of sight. I’ve had several failed and one successful pickpocket attempts against me. Luckily the successful one got only 30,000 cedies (a few dollars). Also watch for crotch-grabbing perverts.

When sitting in traffic you can get lots of shopping done as people come to your window selling batteries, garlic, halogen lamps, towels, toothpaste, health creams, bread, water, snacks, thighmasters, etc. etc. Just make sure you have roughly the right change otherwise the poor vendor may have to chase you for miles to give you your change once the lights change. Some vendors will even come onto the bus and make an elaborate pitch selling the greatest things at the best prices guaranteed.

The Captain

Meanwhile David had arranged for our free accommodation with Captain, who refused our offer of rent because it would be a betrayal to all the kindnesses he had received during his many world travels. “Believe me,” he said, “every time I travel I end up in someone’s home!” Everything the Captain says is an exclamation point.

“We have seven rooms and just us,” he added, neglecting to mention (as people often do) their ten-year-old nephew Little John, whose family is too poor and large to send him to school, so he lives with the Captain, does housework and in return receives room board and an education. How he finds time to study when he spends every waking moment doing domestic labour or being barked at to do more is beyond me.

So, we moved across town to what the Captain calls “the slums,” where we live in a 7-room house surrounded by walls covered in upturned shards of glass. The Captain is liberal only in his love of loudly sharing his opinion. When I told him I had started working at The Statesman he suggested that I demand a driver and payment in US dollars, thousands of them per week, more than I made in Canada. He has no qualms about expressing his displeasure with our friend David, whom he thinks is using us to build his own status here. “I gave that financial support to go to Canada,” he told us. “And I never hear from him again, no ‘hello, how are you?’ from him until he needs something from me.” The Captain yells and his wife Sarah barks; their daughter, who has moved back home, squeals like a psychotic infant on steroids. On our way here Captain had complained about the noise of the neighbours, but the only noise we get here is internally generated.

In the living room two of life’s great luxuries are almost always running: air conditioning and a maximum volume television. They are off when the power is out, which happens every sixth night in this part of town in order to save power. (Excluding personal generators, there is one source of electricity in this country: one dam in the Volta.) The sixth night comes without power or sleep because without our fan heat and mosquitoes get the better of us.

Aside from the treatment of Little John, these are minor annoyances and we have certain luxuries here, like our own private room and a bathroom we share with Little John; access to the kitchen and the Captain’s extensive DVD knockoffs from China, where he tells us you can see the best acrobatic acts in the world so don’t even try to tell him about Mongolia.

Living in gated comfort in a city with so much need is a great source of guilt, so we comfort ourselves with the knowledge that so far we are giving our free labour and maybe we will donate the rent we would have been paying to a good organization, sort of buying our conscious I guess.

That first night the Captain complained that his farm labourers, who are paid by the weight they pick, will always cheat given the chance. He has since told us that African culture is bullshit and that Arabs are not human – funny opinions for an African who makes his living via an Iranian merchant ship. “What would Woody Guthrie do?” Miia asked me. I told her Woody never went to Africa.

Teeth

Right before I left Canada I got a filling and that tooth has been hurting ever since. Miia’s Uncle Lauri in Finland, who is a dentist, took a look at it and found nothing wrong, but somewhere in Russia the pain became pretty severe. I picked up some gargle in Mongolia and cream in Japan, but soon a lump emerged from the gum. Finally in Ghana I made an appointment with a dentist recommended by our guidebook.

“He’s probably friends with the author,” Captain bellowed. “He’ll charge you US dollars! Go to my dentist and pay in cedis, he has taken good care of me and my family!” Captain’s dentist, who really is very good I think and takes the time to explain things to me, quickly determined that the filling had been set too close to my gum and infected it, causing the lump and the pain. I’ve been on antibiotics ever since with some improvement, but I’m likely looking at a root canal in the new year.

International Solidarity

We have been on the lookout for ‘international solidarity workers’ here, i.e., people who care about people and the planet and are volunteering or working to do something about it. We even visited the Canadian embassy with vague daydreams of a cocktail reception with beavertails and poutine. We were sorely disappointed when there were no other Canadians there, not even on staff. We enjoyed a little AC as we filled out a form, and I saluted the flag (half mockingly and half homesickly) on the way out of the compound. The guards thought that was pretty funny.

The guards there, despite being Ghanaian, were laid back Canadian style with no guns. On the streets however I often see cops carrying rifles around, which is a little disconcerting. These are very young men generally, and even the military is barred from carrying weapons in public here. Fortunately, aside from traffic bribes, the cops here are not so overtly corrupt and don’t throw their weight around. There was a National Reconciliation Commission two years back and its recommendations seem to have done well to create stability and harmony here.

And just that afternoon we finally met some of those international solidarity workers, Tim from the UK and Megan from the USofA, who are paying to volunteer in a village for several months. The four of us popped in to see the launch of a new web site called Stop Killing Us, about climate change in Africa, which should have been interesting but consisted of watching people scroll through the web site while eerie music played. We invited our new friends to join us in visiting Dacosta and WO (warrant officer) for dinner at Burma Camp but they had to get back to their village.

The food at WO’s place was familiar and it turns out WO’s wife cooked all our food during Mercy’s funeral, even though several other women had taken credit for it. During dinner we met WO’s brother, an electrical engineer, who told us all about electricity supply in Ghana before retiring early. WO told us about Lebanon, from where he recently returned. “What happened there was terrible,” he confirmed. He’s been a soldier for more than 30 years and has survived too many dictatorships to count; he’ll retire soon. I told him and Dacosta about how my grandfather was in the air-force and was in WWII and they thought they had misunderstood when I told them his age. There are very few 90-year-olds around here.

We chatted politics briefly while watching the evening news, which focused on HIV and agriculture because it was Farmer’s Day in Ghana and AIDS Day internationally. It was pleasant and easy but as usual the transfer of information was a challenge because of language, cultural, and knowledge gaps. We know so little of this place and they know so little of ours, and they probably aren’t used to being asked so many questions.

The Statesman

I met the chief editor of The Statesman on Friday and started working there that Monday. He liked my credentials and thought I might help start a development desk, get some good stories and build contacts with district governments throughout the country. He introduced me around a bit and I met the editor, a woman from the UK who has been with the paper just over a year, the cartoonist, and the “youngest” staffer, the sports editor who everyone calls Uncle.

On Monday I met the rest of the editorial staff in a supposedly daily editorial meeting tentatively scheduled at 11 am. In reality, most days there is no editorial meeting. Mostly we discussed the special xmas issue coming out on Dec. 22, used largely to draw advertising revenue because the paper, which only recently went daily and is still running at a loss, hence my lack of pay. I’m okay calling it a great learning experience for now. It also gives me credibility and access; next week I will be interviewing the Attorney General and the national Chief of Chiefs. Even among my Ghanaian friends I feel like this work has earned me a new level of respect and understanding of what I’m about and what I’m doing here. Patrick in particular, who has always given me much respect, is a big fan of The Statesman and is a member of the ruling political party. He read my first editorial while I sat with him on a Tro Tro and was duly impressed. He promptly opened up to me about the need for good business practices in Ghana and to allow for leadership from the grassroots, politically and in business. “People are suffering,” he told me, “and they need to be heard.” He explained that in Ghana business is based on relationships and making the right impressions, but stressed that while he’ll grease the wheels with his charm he has never paid a bribe to get a contract.

According to Patrick and many others I’ve spoken with, The Statesman is a highly respected thinking person’s paper that shuns stories of petty crime and entertainment news (except in the weekend edition). At the same time, it struggles to be seen as truly independent from the ruling National Patriotic Party (NPP), which the paper supported long before it became government. It is supportive but does not pull punches when criticism is appropriate.

The editorial meeting though soon deteriorated into a series of complaints and questions: why doesn’t our unused vacation roll over into next year and how are we supposed to work on a special edition in addition to putting out a daily? The chief editor crushed all complaints in a lengthy lecture about being a team and following policy, during which he singled out several people who had offended him in various ways, leaving no room for dissent. All those lessons I learned about cross-cultural business came flooding back and still did not adequately explain all I was seeing and have seen since – it’s a different world.

Right away I was thrown to the wolves and given the task of interviewing Ben Ephson, editor of one of about 30 competing newspapers in Accra, about a very unscientific survey he did predicting the next president to be elected in 2008. “Hello Oburoni [White Man],” he greeted me, “have a seat.” He had the air of a big man was determined to let me know it. On the way over in a cab with an office boy as my guide I had quickly read Ephson’s pool and tried to memorize the names of the 16 candidates running for leadership and jotting down questions to ask. I guess I did alright because a beefed up version of my story was the lead story the next day. Miia and I celebrated with coke and red red (beans and plaintain).

Since then I’ve been writing every day, sometimes a little and sometimes a lot, and inviting large companies to pay to be featured with a story by me about them in our xmas edition – this is where commission could come in but I think I prefer writing for free than pitching for money.

Little John

We spend a fair bit of our time with Captain’s nephew, Little John, fighting for the right to do our own dishes – so well trained is he that he anticipates our needs before we dream them, brings me ice water after seeing me root around in the fridge unsuccessfully. He doesn’t understand that it is awkward for us to be so well served by a little boy (or anyone really).

He is as sweet and kind and hardworking a kid as anyone could hope to meet, yet I’ve never his “parents” praise him, only bark orders. Wondering if maybe we were being cultural fascists in judging Captain and Cynthia harshly for their treatment of Little John, Miia and I have each discussed the situation with other Ghanaians.

“I am opposed to that,” is what Patrick said to me, and Professor Apt said about the same to Miia. Patrick said no matter how poor he was he could never fathom letting his child go be a labourer in someone’s house. “They have no childhood,” he said, and Professor Apt has trouble remaining friends with people who have ‘foster children.’ Still, we know that Little John would have a very difficult life back in the village competing with his siblings for food.

I do feel that our presence here is good for him, if I can be so arrogant, because we are constantly giving him positive feedback and Miia has managed to get him laughing with a never-ending barrage of pokes, tickles, squeezes and jokes. He seems to like us and we like him a lot.

On Sunday we awoke to the 5 am drum parade circulating around our door, which was good preparation for a four-hour church service with three offerings, during which the preacher preached about how we are no different than madness with our clothes unfit for public consumption. “If he treated his first wife that way he’ll treat you the same; don’t believe his smooth talk!” he admonished us as we sweated in our tight white traditional funeral wear, up front and centre under the light of the videographer, projected onto the big screen TV. During the collections he reminded the congregation that believers give generously.

Patrick made no qualms about explaining the service. “All they want is money,” he said. “People here living hand to mouth in abject poverty and they have three offerings! Keep us in church for four hours.” He’s a believer but he has his limits and he doesn’t understand how so many different races could all be descendant from Adam and Eve either.

We relieved our post-church headaches in a dance with David’s nephews and nieces, Bernard, Evans and Albert and the twin girls both named Albena, with whom we exchanged moves and drew a crowd until David’s drunken cousin gave us the old pinch, a hard one. We asked David to give him a little talk, which David did very publicly before sending him home for the night, leaving us to sheepishly sip our cokes in the courtyard, where the kids raised Cain with paper airplanes and cranes made by Miia. Bernard sat on my lap and I snuck him sips of my coke (such a delicacy is not normally wasted on children). When I told him to share the remainder with his friends a near brawl ensued, and somehow David’s son Sim was at the epicentre. “That boy is mad,” said Bernard. Sim’s culture shock seemed to be agitating his ADD and none of the locals’ efforts to teach him good Ghanaian manners seemed to help much. A few piggyback rides distracted the kids from their problems.

We ate dinner with Dacosta, who loves the village food because it is so much fresher than in the city he now calls home.

Producing and Exporting Countries

After all the official things we had the chance to linger in bed and talk politics to the backbeat of the usual Christian music from the electronics store. “Why don’t all the cocoa, coffee and sugar producers create a CCSPEC and take Nestle over, drive up the prices on our non-petroleum addictions and make more money for the farmers.” That kind of nonsense. “Funny how cell phones make sense here and have brought people together, but they still exclude rural people who don’t have money and can’t get signals.”

Eventually we made way to see the Chief, passing a hoard of pre-schoolers on the way who made up a song: “white man give me money.” Their voices were beautiful until someone explained what the words meant.

We discussed the latest of David’s brain children with the Chief: he wants to start an organization and build a community centre, and we agreed to chip in a few dollars. Somehow this small gesture led to the Chief offering to make us Sub-Chief and Queen Mother, an offer that came with a lesson in the Chieftancy system (a subject on which the Chief has written a yet unpublished book): they must maintain political neutrality with no partisan affiliation, yet be judge jury mayor and planner for their village. The Chief is accountable to the village elders, who chose him and can remove him any time – unlikely in this case because he has served as Chief for 40 years. Society is patralineal with tremendous importance placed on clan or extended family. No one is without a parent: David has just inherited his father’s sister as his new mother. Age cannot prevent parentage; in some cases your father’s brothers little boy is considered your father. This way people are cared for all their lives; they are never alone and, from the North American point of view, they never have privacy.

By the time we left the Chief we had somehow committed ourselves to return for a ceremony in honour of our small gift toward the community centre. We thanked him for his lessons and his time and Henry took us straight to the senior secondary school, where the security guard had more time to kill than intruders and had landscaped himself a rock, sand, grass and shrub garden, which he took great delight in showing us. When we found the principal he was quick to announce, “We are a deprived school with many needs: lab equipment, books, uniforms.” The school receives little government support and runs mostly from school fees, which prevent many of the villagers from gaining an education beyond primary school. My internal calculator told me that the money required to educate every child in the village would be a few tens of thousands of dollars a year, and I wished I had that much to give or that I could devise an effective educational system that doesn’t require books, equipment, uniforms or buildings, only teachers. But I’m much better at criticizing pedagogy than inventing it.

The mild depression induced by the principal was quickly cured by the students whose classes we visited briefly. They were full of enthusiasm for life’s possibilities and asked us questions like ‘are you married?’ and ‘do you use chemistry in your life?’ We promised to return with addresses for Canadian universities so they can send away for application packages.